|

|

|

|

|

|

CONTACT US |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Private First Class Charles Edgar Barnhart,

earned the Silver Star medal,

and the Purple Heart.

An edited transcribed memoir from family recordings follows;

The majority of blue font captions are comments from the family.

“ We lived in the country three miles south of Columbia, Missouri. I went to a country school (Bethel) and my sister, Opal, was 4 ˝ years older than I. The year that I was 4, I went to school with her every day. The second year, when I went back with her again, the teacher said, “If you’re going to be showing up every day, I’m going to enroll you.” Consequently, I started school at an early age, and was a year ahead of the rest of my classmates. I ended up finishing high school just before I became 17 years old, in May of 1942. Since I was planning on attending the university in the fall, it was necessary for me to take a correspondence course in advanced trigonometry in order to enter the College of Engineering. I also spent the summer working for the Stephens Publishing Company. This, along with dating Reba, kept me busy all summer. In the fall of 1942, I entered the University of Missouri and joined the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity. I am sorry to say that I didn’t take advantage of this year, BUT I CERTAINLY HAD A GREAT TIME!” .

“On my 18th birthday (June 2, 1943) I registered for the draft—had to—it was the law. Needless to say, the army was glad to get me. With tearful parents, Reba (later his wife) and cousin, Billy Vernon Barnhart, I boarded a bus and left for Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to be inducted into the Army on September 9, 1943. Took a bunch of tests on everything you could think of.

|

|

"I thought the Air Force (U.S. Army Air Corps.) would be nice, but I couldn’t hear the different sounds (possibly because of tinnitus, which I still have) – could not qualify. So after about three weeks, I was put on a troop train and traveled to Camp Blanding, Florida for basic training. This was a great experience! I had to dig foxholes in sand where the holes would fill up with water – snakes and everything! They also shot live ammunition over you once in a while. I slept in a barracks with several other men. They tell me that every morning the Charge of Quarters would come in, stand by my bed and yell “Everybody Up!” That’s what I was told, I never heard him. One morning while I was on KP (kitchen police) a friend came in and said that they were recruiting for the paratroops. I said, “No thank you”. But my buddy finally changed my mind….to make a long story shorter, I passed the test for the paratroops, but my buddy didn’t. After 16 weeks of basic training, I was sent to Fort Benning, Georgia.( jump school) The training was tough, but I wrote home to Mom and Reba that the “jump suit and boots were really something. I was so proud to wear them – best uniform in the whole army."

"After four weeks of jump school, Charles receives his paratrooper wings on March 13, 1944. In a March 17,1944 letter, Charles mentions he is attending a demolition school working with plastic explosives. On May 19th he writes his last un-censored letter, traveling to New York, to ship out."

“Arrived (in Scotland**) on June 6, 1944. Had my 19th birthday on the way over. Came on the luxury ship The Queen Elizabeth. Took 9 days. We were put on cattle barges and sent back off shore.” ** The webmasters father, Pfc. F.X. Schweikert was also aboard the Queen Elizabeth.

"In a letter to Reba, he said that there was no doubt that they were cattle barges, and had not been cleaned prior to their use that night as sleeping accommodations."

“We came back to land the next day, and were in the southern part of England. We had no idea that night was the beginning of D-Day. Airborne went first – our outfit had already jumped in France. It was a night jump and got them badly scattered. A lot of fighting to do, and I guess I was fortunate to be where I was instead of there, because I have a friend (George Spartichino) from Michigan (George was from Massachusetts, he jumped on D-Day), and his chute caught on a pole and that swung him down hard and he hit the pole hard and he still has leg problems from that (but it didn’t get him sent home). I’m getting away from what I was talking about – but we thought we would be in England and go over as replacements for people who had been killed or wounded but they didn’t. They left us in England. Those who came over on the Queen Elizabeth were together and we had lots of friends. We had to start some training while in England to get us ready for combat – lot of things to learn.” “My first combat was in Holland…”

|

|

"Operation Market-Garden was the code name for the invasion of Holland (Netherlands). Market was the airborne assault and Garden the ground assault. In Operation Market, over 30,000 men from the 82nd, 101st, and British 1st Airborne flew out of England and jumped into Holland on the afternoon of September 17, 1944. “H” Company, 505th Parachute Infantry, touched ground at Drop Zone “N”, just East of Groesbeek."

“…. the Germans were threatening the area – we flew in, landed, and took the land.” The two I remember getting hurt were by anti-aircraft fire that caught their chutes while they were in the air and both of them were killed when they hit the ground, but mine was almost incidental. When I got my shock from my chute opening, my rifle tore loose and went down to the ground and I watched it and tried to follow it – I tried to use my chute to keep up with it – and then I landed and took a short circle and didn’t see it and took a bigger circle and didn’t see it and I was running looking for that durn rifle and a guy that I learned to really like, Moose Gamelcy, they called him “Moose” because he was rough and tough. He had been behind me in the “stick” when we came out of the plane, and he wondered what in the heck was wrong with me and I told him I had lost my rifle and he said “Son, quit running around and let’s go down and get you another one.” We had equipment bundles that came down with us, and I knew that, but I really hadn’t thought about it. Anyway, I got another rifle – it turned out to be one that had been lost in France and recovered and I had somebody’s rifle that had been in our outfit – had it for quite a while. I feel like I’ve jumped some spaces I should have talked about. One other thing, we had the parachutes and we also had guys that came in in gliders. They could carry a little bit different stuff that we couldn’t carry in our planes. I watched a glider come in at an up-hill situation and it wasn’t good for the glider because it couldn’t climb without a motor. I watched it go over me and as it got close to the ground, it went into the ground and tumbled over. I had things to do and couldn’t spend much time with it, but I did run over to see if somebody was hurt – and they were- but they weren’t killed. They were just trying to get their stuff out of the glider.”|

|

“I had been given a bazooka assistant assignment. Another guy had the bazooka and I had the rounds for it and I had to get those out of the equipment bundle, find the bazooka man – I didn’t find him for two days!

We got organized and started moving and we took over and it was almost incidental by this time. I don’t know, maybe it’s confusing when you see that many airplanes and that many people coming out in parachutes and coming in. I didn’t know exactly where or how we were going to land, but the Germans seemed very confused…... In fact, I never fired a shot and we took the town (Groesbeek). We had been walking quite a while, later that day and went into another town (likely Nijmegen).” “They told everybody to sit down and take a rest. I was on a street and had just sat down by the gutter and a guy just a little way down the street yelled at me and said, “You’ve got a grenade under you!” A German had been down in the sewer system and he had pushed the durn thing out into the street and it was just a matter of two or three feet from me and, of course, I moved real quick! But it didn’t go off…. it didn’t explode. I got hit by one later, but that’s another story. We took the town; the Germans seemed to just melt out. They weren’t prepared to fight at that time.”

“When we jumped, everybody carried a land mine, things to blow up tanks, because they knew that the Germans had equipment around there. My squad sergeant told me to come with him, we were going out. The British armor was to come in and we didn’t know exactly when and we didn’t know if it would be that day or the next day, but we had to set up an anti-tank position in case the Germans came through and had to have somebody there in case the British came through…. We could stop them from blowing up their tanks. He had things to do and he told me to dig us foxholes…get ready for the night and I had a trenching tool – they were rather small little things that broke in the middle so you could bend them and use them to dig. And I started where he told me to go and he left. I had just started digging and here came an ol’ boy, carrying a long handled shovel. He was also carrying two bottles of beer. He was a Hollander. They did not like to be “Dutch”. Dutch became “Deutsch” which was “German”. He came over and handed me the two bottles of beer, motioned me over to a tree. That’s what I did – I took the two bottles of beer, went over and sat under the tree, drank the beer and he dug me a foxhole. I would have liked to have been able to spend a lot of time talking to him, but there was always something that interfered – couldn’t speak the language for one thing. But, at that time, I was alone and after he dug the foxhole he took his shovel and went home.”

“I was the assistant bazooka man. The bazooka man hurt his back – I always wondered about that – but I never saw him again. I got the bazooka and became the bazooka man. If you don’t know what that is, it was a rocket that you fired off your shoulder and basically it was intended for cars, tanks, whatever was moving. When you fired it, you held it over your shoulder and it was ignited from the back and sent the rocket where you aimed it. Anyway, I got the bazooka and it was that way until I was wounded about three or four weeks later.”

|

|

".......In terms of people, one of the ones that impressed me was our platoon Sergeant. His name was Elmer (Blubaugh). He was in charge of a bunch of us and he was irritated many times a day, I am sure, but when he needed to talk to you, he talked. The couple of times he wanted me to change my way about something, he told me and I understood and did it….he did not blast out. He was in service about when the war started I guess, because he had been in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, Normandy, (and now Holland). I thought he was the greatest. That’s all”.

(Sergeant Blubaugh, a four combat jump paratrooper, was considered one of the old men of company H.)

Anyway, we were on the road block and they knew the Germans were coming. They didn't know, of course, just how the Germans would do it. Elmer had things set up as best he could to counter them as they tried to get in. At our roadblock we should have had me with my bazooka, my assistant (James A. Wambach) who would fire it over my shoulder, he also had a regular army rifle, I also had a pistol and with us was my good friend Sparty (George Spartichino), who was a BAR(Browning automatic rifle) man, he had an assistant who carried a regular M-1 like my assistant did. There was also a 1st Lieutenant"

(Charlie speaking of the 1st Lieutenant) "He had jumped with us. He claimed to have a bad knee, so he caught a ride on a plane that was bringing in equipment after we were there. Then he wanted to take over and run the place. The night I was shot, that day he came through and started changing Elmer's plans. Elmer got word on that, and I happen to be there, when he proceeded to straighten that 1st Lieutenant out. Elmer never got bitter with him, but he let him know who was in charge – and it wasn't the 1st Lieutenant.

“ As the bazooka man, I was in charge of our position. But before the first shots were fired, that 1st Lieutenant, without our knowledge – he didn’t say a thing to us and this was a night attack, he took the BAR man who should have been there with us and the other two riflemen that were there, and of course he should have been there with a gun, too. We hadn’t counted on him anyway, but he took these people and bailed out. Left two of us on a roadblock and the Germans coming in. The Germans had been in this country – they knew pretty well what it was and how it was laid out, but they were coming down and they started across the white gravel road. It was a night attack, but you could see them. As individuals you couldn’t see them, but in the white, almost glass-like stuff you could see them. I thought it would be a good time to use the bazooka to see if it would do any good. The first shot down there was my bazooka, and fortunately I hit a German right about his knee and it exploded. The bazooka was made to hit tanks and solid objects, had I hit him in the stomach or some soft area, it wouldn’t have gone off.”

That’s where the game started and I knew in my own mind that I was going to die because we knew that there were a bunch of Germans and that road was a typical country road. It looked bad, a lot of them - and just two of us, I figured that this is it – this is the time I’m going to die because there is no way in the world that we can get out of this. It’s when I realized something that’s been good for me ever since, I wasn’t afraid to die. I don’t want to die, but to get caught up in whatever, dying is something you’ve got to face I guess, and I did have to face it that night. We didn’t have anyone around us anywhere. “The Germans holed up for the night in a burned out building across the road and I knew there were a bunch of them in there and another place that had been dug out by somebody and had a door in it. I tried to hit that door and blow it up, and I never could. I did fire several rounds into the brick building and I know it helped keep them confused as to what they had because the way they threw their grenades at me they thought I was way on back because the bazooka had a blast that went out behind when you fired it off. It was on my shoulder and when I was getting the power to fire it, they threw those grenades over there. I know we would have been wiped out if it hadn’t been for that bazooka.”

“They kept throwing grenades at us all night that night and they kept throwing them over our heads and back behind our foxhole. They never crossed that road – it was not ten feet wide maybe. One guy did come across it. Looking at it later thinking about it later and I thought about it many, many times, he knew where he was and what he was doing. He was shooting at me and I knew it, but I couldn’t find him- couldn’t see him well enough to try to get a shot at him ‘cause I had a pistol besides my bazooka and you’d hear the bullets go over your head and I knew he was there and I had my pistol out and ready to shoot. I stood up a little higher and leaned out a little further, looking for him and that’s when he saw me, I guess. The son-of-a gun got the grenade in front of me. ("I ended up with a bunch of very small pieces of metal, gravel, and grass.") The German grenades were different than ours, it didn’t throw the metal out that ours did, but he got it in and I didn’t know it – I swear I can’t tell you – it had to be done first because after that he had a Schmeisser (MP40) machine pistol which was an automatic pistol and they were very effective and he got me three times with that and as it worked out, and I figured this out through the years, that he actually fired three rounds which is not much (an MP40 cycled at about 800 rounds per minute) I was lucky that he stopped, the clip ran out or something else – whatever did it, one bullet hit me in the wrist and I was bothered pretty bad, because I could see the bone and I kept thinking I’m going to have a bad wrist. Another one went, because I was holding the pistol up looking for him, went through the muscle of my right arm and then on into my chest and the one in my wrist went into my chest and another one that didn’t hit something else first. Anyway, I got hit five times with three bullets. I was really injured but I didn’t know that – well, I did. I knew I was spitting up some blood, but not a lot. The one that hit my wrist had cut to the bone – the white bone was shining in the moonlight…I thought my arm was going to be ruined – I don’t know why I was worried about that.”

“That night, my assistant Wambach, bandaged me up. I was still on my feet and useful and at the time everyone carried a shot of morphine and he gave me my shot and later on gave me his shot and that probably effected my actions the rest of the night. He told me to lie down, and we were in a foxhole, well covered and protected. It would have taken a direct hit into the hole to hurt us. I went to sleep and we had a patrol come in to see what had happened. Everything was so quiet by then that somebody got the report back up to headquarters that we had been blown out and so they understood the Germans were where we were.”

When I woke up that morning, some of the guys had come down to see what was going on and so we started gathering Germans. The first shot down there had been my bazooka, and fortunately I had hit him right about the knee or it wouldn’t have gone off. But I looked at it the next day and it (the German) was literally blown to pieces and it killed two more that were right beside him apparently by concussion. They showed no holes or wounds in them. So we started gathering up Germans, and I couldn’t believe it – we had forty-some live Germans, and just the two of us – and I had killed three with the bazooka and he had shot a couple with his rifle. They lost their fire – they had just quit fighting. All that night I kept thinking all they had to do was come across that little, narrow road. I’m glad they didn’t – it could have happened so easily. That’s my big experience in war and I had many more, but none came as close to killing me as that one did.”“We were under observation from the German side, so they could not bring in a car or anything like that to get me and everybody thought I was hurting more than I was, so I just walked back over the hill toward our platoon command post and nobody tried to shoot me and I got to the command post and the medic looked me over and said my buddy had done a good job, didn’t need to change it in any way.

“Our Company Commander knew the First Lieutenant, and apparently didn’t like him. Word got back to him that he (the Lieutenant) had bailed out on me – the Company Commander said that he had done the same thing before, and didn’t know how many people may have been hurt, killed, or maybe captured because of his actions.” “The Lieutenant was a plain and simple coward.

I had to get in a jeep and go back to the field hospital – nice little ol’ ride – I didn’t want to lay down so I sat in the seat next to the driver and talked to him. Nurses took over at the field hospital – I did have a punctured lung – came in with a litter thing for me to be operated on – I said I didn’t need that thing “Yes you do, you’re going to be operated on it.” I lost that argument. They operated on me and I came out of it and I was back with the nurses and wanted to know what I was going to be like and the Dr. came by and said we were trying to get the bullets out and figured out we were going to do more damage than good, and I’d be better off to let the body form a cyst around them and that will help protect you. So they loaded me up and sent me to Belgium, to an English hospital. (Came into contact with a nurse that wouldn’t take care of his needs) was supposed to bring me a bed pan in bed and she wouldn’t do it and as soon as she got out of sight, I got up and went to the bathroom. Never really forgave that nurse. After a while some British came and they pushed around on my back, testing to see if I had fluid in my lungs, which I did later on.” “So, I was in the hospital – got out of there and was very glad to get away from that nurse. They took me to a plane on a litter, because I had enough wounds that everyone was concerned about how I was going to last, and to me, I had not wanted to do anything except to walk around and talk. Anyway, they got me to an airport and flew me to England and there I ended up in a good ‘ol American hospital that had been put together in England. Everybody had internal injuries of all kinds. One of the guys there said, “You’re lucky, the guy died last night that was in your bed!” It turned out that they had diagnosed what was going on, and everybody had to start doing calisthenics. Well, at that time, they didn’t want me up, but I had to do calisthenics in bed…my right arm was shot up and my right lung was punctured so I had to lay on my back and lift my left arm up and back, up and back. But the man who had died had been fine, and he was showing recovery except that he had been lying down for days and a blood clot had come loose and killed him. Consequently, they wanted everybody to do the calisthenics so they wouldn’t have any more damage from blood clots.”

“The day I got there they had two doctors (officers) standing beside me and looking at me and discussing what they were going to do. I can’t remember exactly, but one said “We are saying that in thirty days we’ll have him back on his feet.” They argued while I listened and I was really pulling for the guy sending me home, but as it turned out, the higher rank got his way and I was in England for a while. I was up and walking soon. I decided that I was really getting better, my lung felt so much better and this doctor was nice – he came in with a big grin on his face, with big needles. He came in with three nurses, one with him, one came up beside me and put her hand on my shoulder, the other one came up behind me and put her hand on my forehead. He started to put the needle in my lung cavity because there was blood and fluid there that wasn’t supposed to be. That was why I felt better – my lung wasn’t hurting because it had collapsed. I was living on one lung. He came out with a needle that looked about three feet long! He stuck it right under my right nipple between the ribs. He gave me shots as he went down, to kill the pain – and it didn’t hurt. But when he pulled the syringe off of the top of the needle, blood squirted all over him, down on the floor beside my bed! After that he removed the fluid one syringe at a time. He removed about three liters in all. When he did that, my lung started to work again, which meant it hurt. Then I had to do therapy to make it work. I fooled a lot of doctors since then because I still have a lot of metal in my lungs.”

|

|

While Charles was in a hospital in England, he received a letter from his assistant Wambach. Dad wrote in reply, but the letter came back. James A. Wambach was killed in action on October 31, 1944. Twenty nine days after the night at the roadblock. He was 21 years old. Dad sent the letter from Wambach home to mom. In a letter to her, he wrote: “…I am sending the letter that I received from Wambach (the guy with me when I was wounded) while I was in the hospital. I finally got back the letter that I wrote in answer to his. He was killed before it reached him. He was a darned good guy, Reba, and he did a lot for me that night. He was from Evansville, Indiana, and that’s where his wife was.” Wambach’s letter is dated Oct 28th 1944.

|

|

“Got back at the last part of the Battle of the Bulge and if you read history, the Battle of the Bulge was Germany’s last big hurrah, and it failed, and it was pretty much downhill for them after that. We pretty much controlled whatever we wanted to do because they had really blown their last chances. They tried to go to the Atlantic and stop our supplies, but that didn’t work either.”

“We still had things to do…one of the things to do that wasn’t pleasant was taking turns – was buddy up and you took turns going through doors – and if you went through and if you didn’t get shot, your buddy went through and you stood aside. You went from house to house collecting people as you went and it was scary – you didn’t know if you were going to go through a door and get shot all to pieces. But you still had to do it, because if you left those people there, you had trouble behind you all the time. Taking towns was part of it and this has one of the incidences that has been on my mind forever…I had nothing to do with it, I just turned around in time to see what had happened. There was a kid and he ran from a building and I figured he probably had a pistol in his pocket and was afraid that he was going to get checked over and he started running slightly downhill, and he ran out and at least three guys started shooting and they just cut him in two. I didn’t go to see the body. You know that he died for nothing. They didn’t need to kill him. It has always bothered me – you can think about it and feel bad. I knew that I shot and killed people, but they were looking for me, ready to shoot me.”

The following is an excerpt from a letter he wrote to his mother on June 7th, 1945 from Sissone, France:

“….but I have come to the conclusion that I have had my share of this war. Now I just hope the government feels the same way about it. It’s funny though – even though it feels so good to know that the war is over and you don’t have to fight any more – there is still a ‘let down’ to it. Because there is a great thrill to it. You could never imagine what it’s like to go into an attack – especially in taking a town – when a company or a battalion of us started out. Walking, trotting, running. Your heart in your throat and beating three times above normal. Your knees are weak, and yet you have never had so much strength. You’re scared – you're scared beyond words; and yet you are eager.”

|

|

Following the official surrender of Germany, the 82nd was ordered to Berlin for occupation duty.

“That’s how the war wound down for me. We were putting up with the Russians more than anything else. When we took Berlin, the officials upstairs let the Russians go in first. They came and felt like it was all theirs. Berlin was divided into four sectors: British, French, Russian and U.S. to keep it patrolled. The Russians were the only ones that gave any problems. Guys would make runs to get beer – Germans did make good beer! Two or three guys would get a pick up and always, somewhere along the line, run into Russians who wanted to start shooting at you, to try to make you stop. I never went on a run. Consequently, those that wanted to put their lives on the line would go get the beer. I must admit I didn’t mind drinking it !”

“When we went to Berlin, I happened to be one of maybe a dozen who were appointed as a member of the Escort Company. We had tan uniforms with white scarves and gloves. We had to do a lot of drilling and learning special routines. We were appointed to represent the U.S. in Berlin and it got us a lot of free time, ‘cause there were a lot of times when there weren’t any “big shots” coming through for us to display our talents to. We did all sorts of things – fancy handling of rifles – had to be really good at maneuvering your body. The Queen Anne Salute started with the rifle in your hand, throw it up, spin it around, catch it in one hand with one knee on the ground. Got pretty good at that one.”

|

|

“One day a Russian General came down and after our demonstration, we had a demonstration jump with gliders included. I was on the ground watching and the person in the second or third plane, the designated person to trigger the fall of the equipment bundles – had to be separated so they wouldn’t fall on people – messed up and was late and when the equipment bundle fell loose, it fell into a parachute and as he fell, he grabbed another guy and they both fell right in front of us and both were killed. The gliders had problems, too. I was going to sign up to ride a glider, but decided not to after the demonstration.”

“We were sent home by having a certain amount of “points”. I got 15 points out of the night I was wounded. This, added to what I already had, allowed me to come home early.”

“Because of the weather, I spent a lot of time trying to get home on a ship. Weather was bad. Got on a small Liberty Ship. Sparty and I were still together and we were leaving in the morning. We had gone to bed on board and I had slept fine – naturally. Sparty said “I’m sick. I think I’m sea-sick. Go tell someone to get me an apple or something to calm my stomach.” So I went up to the kitchen and told the cook that I had a buddy that was sick at his stomach. I told him he thought he was sea-sick. The cook said he had a long way to go ‘ cause we hadn’t left the harbor yet! Sparty got the apple and got along OK. I felt fortunate that I never got motion sickness, ‘cause on the way home we got into what they called the North Sea Storms. The next day we were put down below so none of us would get swept overboard. We were locked up and that was interesting to say the least. If anything had happened to the boat, we would have all gone down together. There were other ships that were damaged and people lost. It kept up for several days – some got sick, some didn’t. The water would come over the top and the boat would float – then the rudder would sound up like things were getting torn up – you could hear the spin when the propeller came out of the water…We all survived, but it was not a pleasant experience. We came to Europe in nine days; it took a lot longer to get home. The rest of the 82nd came home in January of 1946. I was home before Christmas, 1945. I am sorry I didn’t get to march up 5th Avenue in New York – but being home early was worth it!”

“I feel like there are things that I haven’t said, things I have forgotten. I have done this in a medical situation where Reba was sometimes not sure if I knew her last name. Anyway, it’s time to sign off on this thing and I don’t have any smart answers to say about it, but I do hope that you will read it and appreciate it. I came through my life without talking about this part of my life. I am glad that I got talked into doing this because I think it’s great. Looking back and listening back, it touches me – I hope it touches you.…………10-4.”

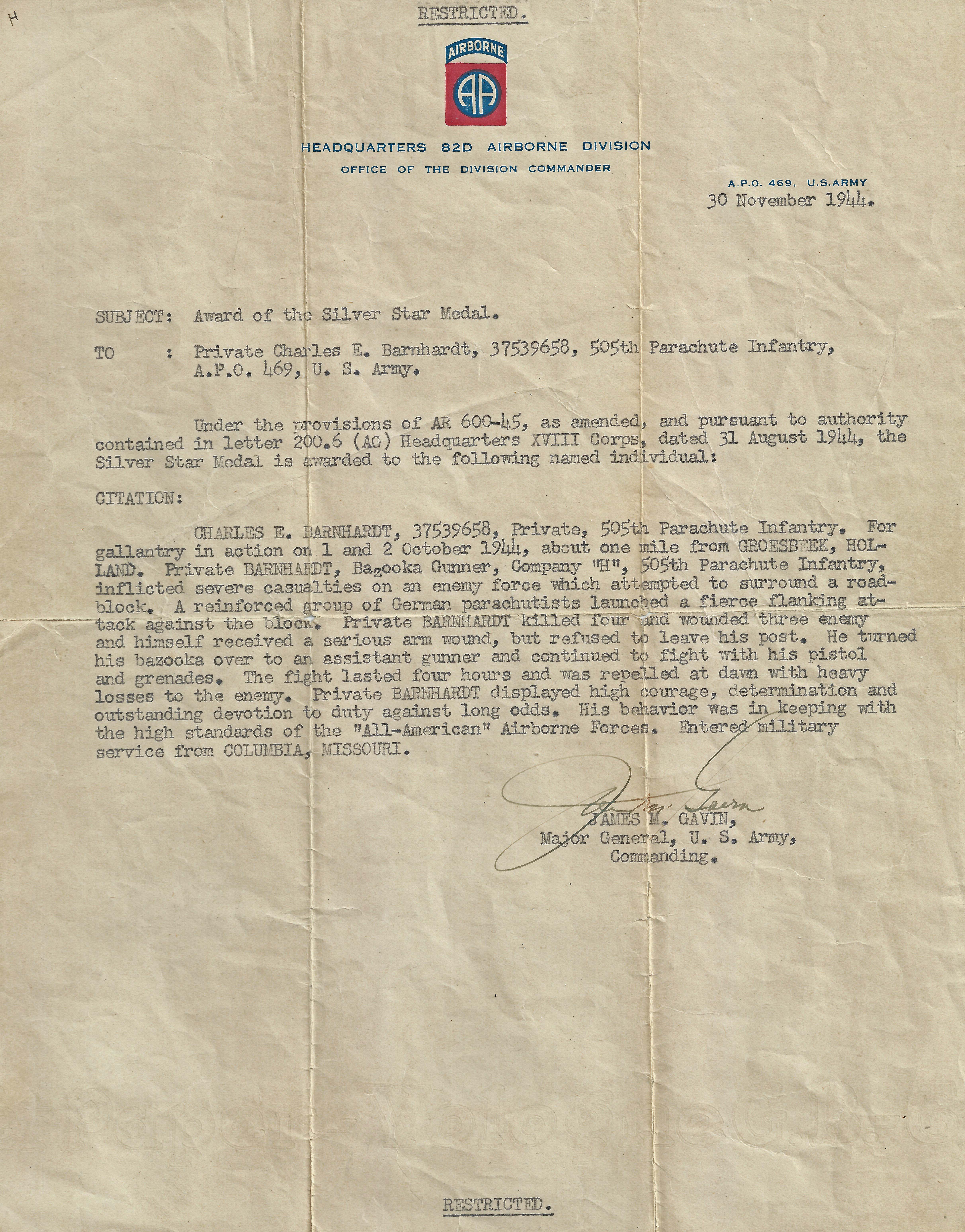

The Silver Star Citation Charles Barnhart earned at a two man

roadblock in Holland. It was signed by Major General James Gavin.

The paratrooper on the right holds the German machine gun(MP-40) that wounded Pfc. Barnhart at the road block, George Spartachino is on the left the other two are unknown.

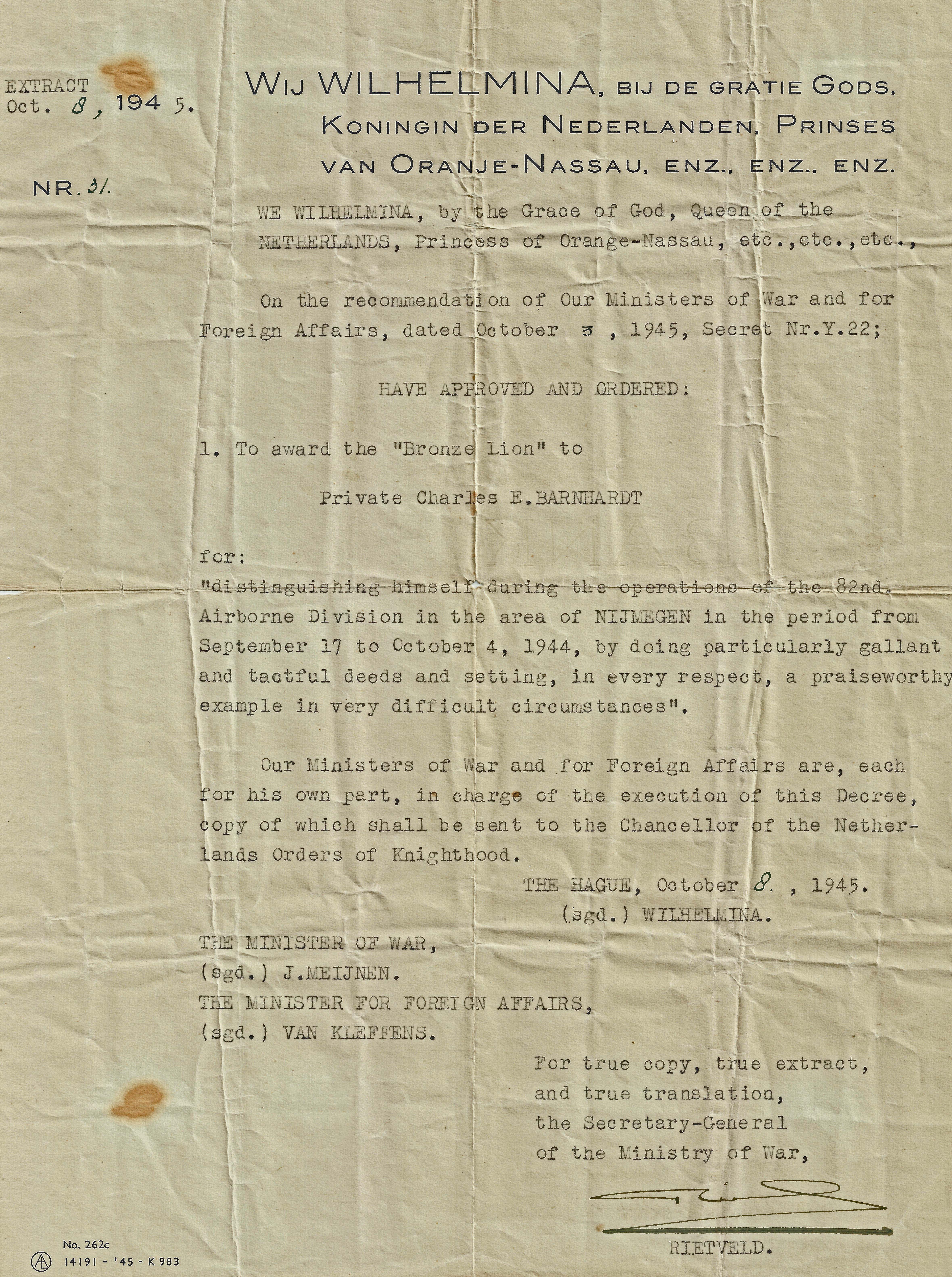

The Bronze Lion medal was issued to Pfc. Barnhart on October 8,1945.

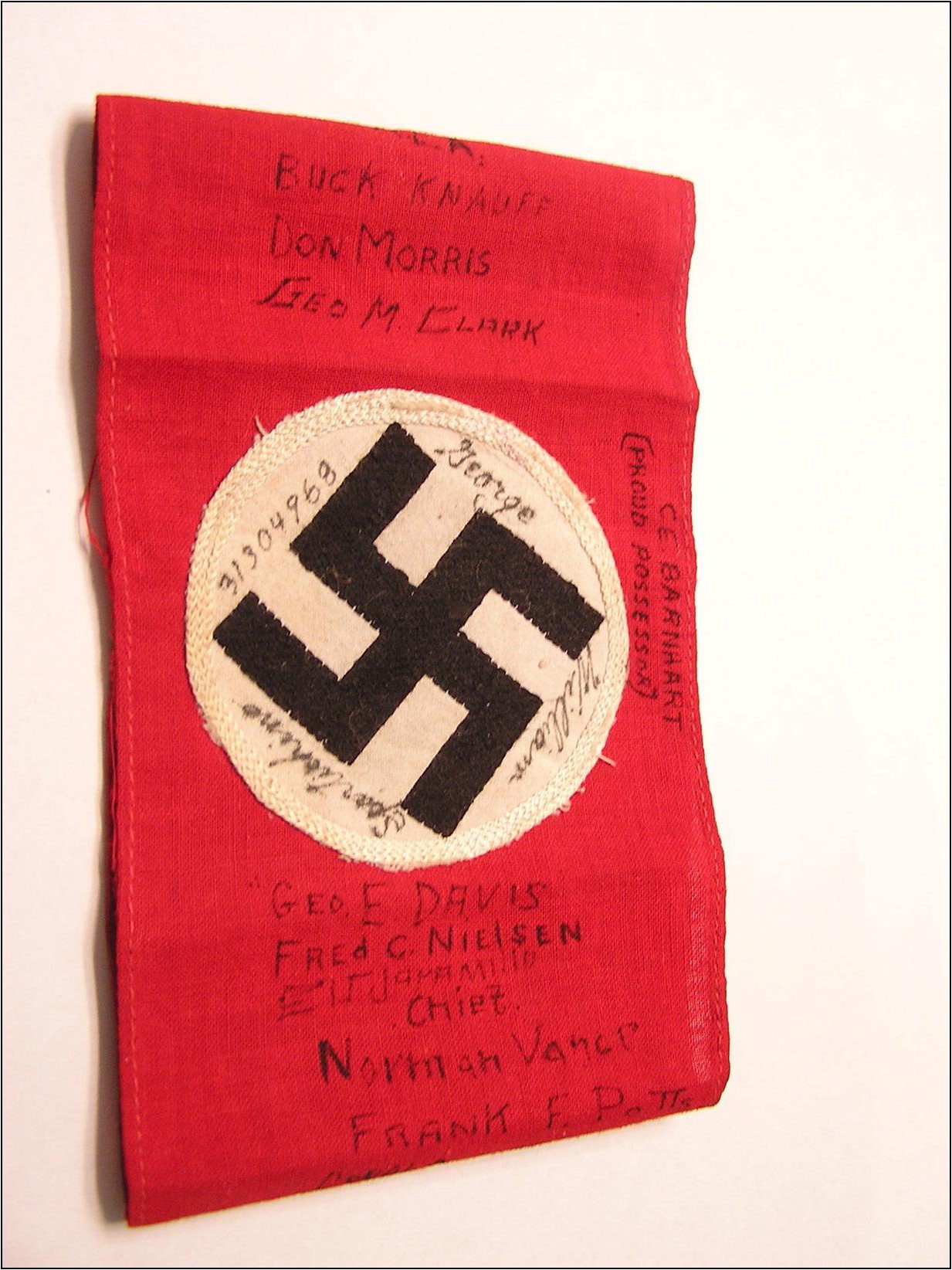

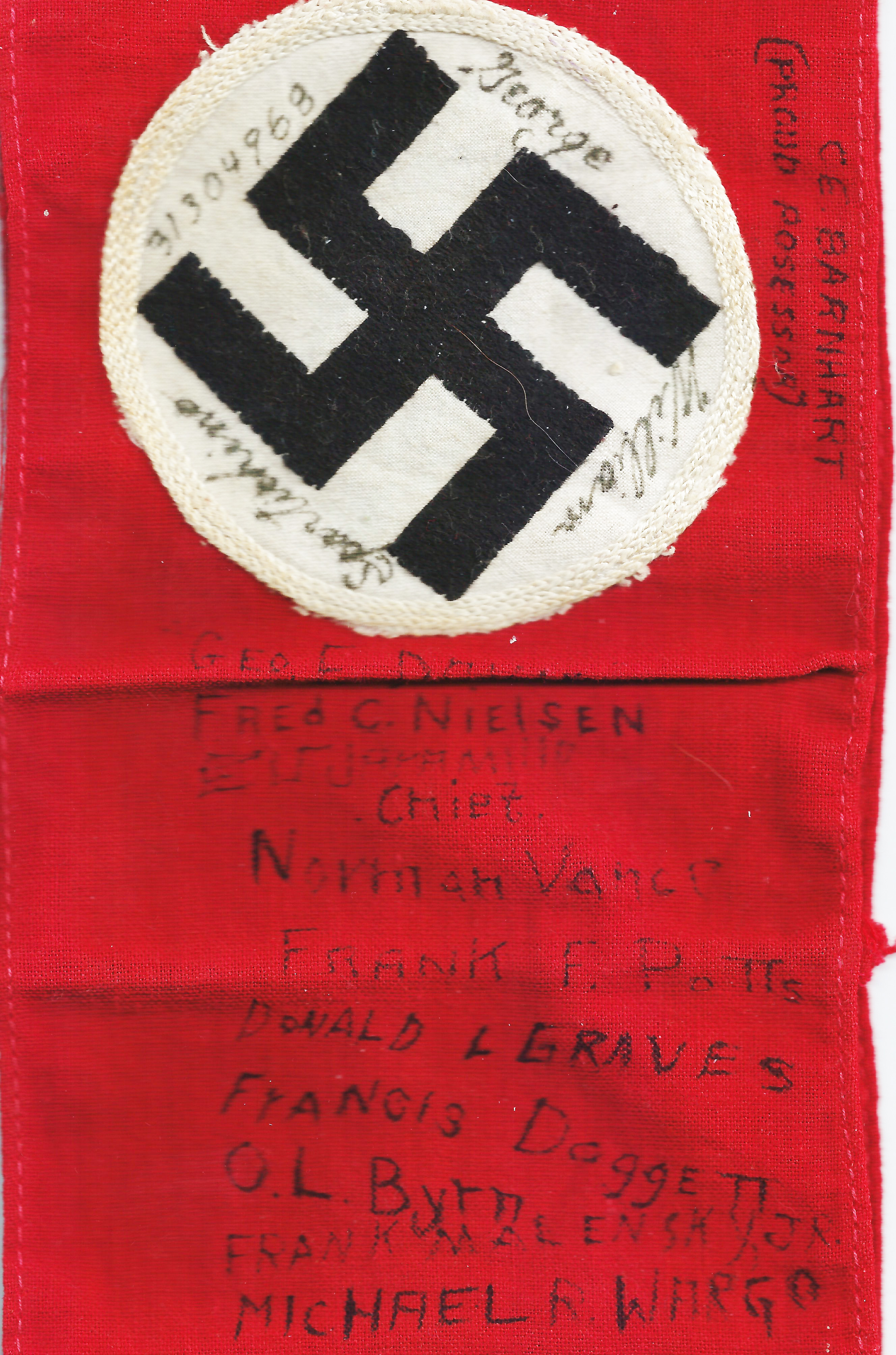

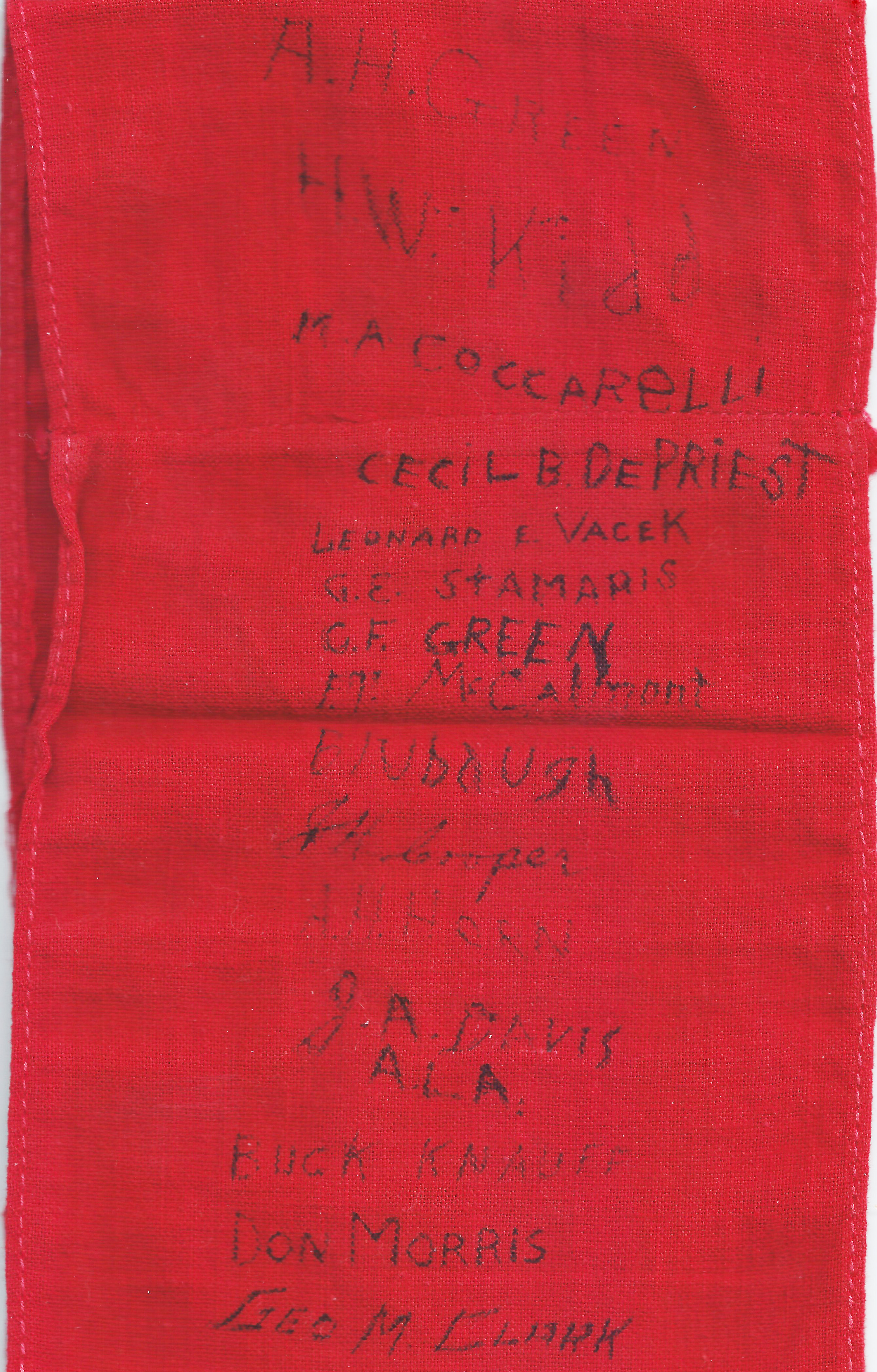

Pfc. Barnhart's platoon signed the armband below.

You can see the entire list of names in the 3 photo

compilation that follows below.

Names on Arm Band as signed (the H company platoon number is unkown),Geo. E. Davis,

Fred C. Neilsen,

E.V. Jaramillo chief,

Norman Vance,

Frank F. Potts,

Donald L. Graves,

Francis Doggett,

O.L. Byrn,

Frank Malensky Jr.,

Michael R. Wargo,

H.W. Shupe, Jr.,

A.H. Green,

H.W.Kidd,

M.A. Coccarelli,

Cecil DePriest,

Leonard Vacek,

G.E. Stamaris,

C.F. Green,

F.T. McCalmont,

Blubaugh,

J.H. Cooper,

A.H. Horn,

J.A. Davis,

Buck Knauff,

Don Morris,

Geo. M. Clark,

George Spartichino.

Left to right, A.H. Horn, G.E. Davis, Lee, "Alabama" (Jesse A. Davis), Oscar L. Byrn,

George Spartichino. Kneeling

is Staff Sergeant George M. Clark.

82nd Airborne Division's Escort Company in Berlin 1945. Pfc. Barnhart is on the right the other two are unknown.

|

|